Everybody “knows”…

…what project management is. And yet, based on my 30 years of management, management consulting and engineering consulting experience, the most powerful and ubiquitous management concept- managing discrete work- is rarely done well.

At the its most fundamental level, most every assignment you have ever been given can be thought of as a project.

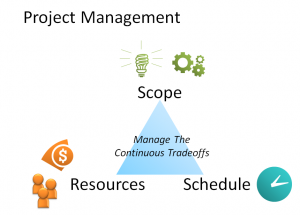

- What you are supposed to do, defines the “scope” of the project

- When it has to be done, sets the “schedule” for the scope to be accomplished

- How much you can invest in creating your deliverable scope defines the “resources“- be it your time, your time with certain equipment, or others’ time either aided or not

So, every activity, project, program is focused on achieving its scope, within a certain schedule while consuming given resources. Project management must be the way to achieve that singular solution.

Project management is…

…the continuous management of the trade-offs of scope, schedule and resources

Full stop. It can be, and it is, this simple.

Many of us do it intuitively, every day. For example,

- How much time do I/we spend proofing this report due next month?

- How many people do we need to build the booth for the church picnic by Wednesday?

- When will you be done?

And because these are one-off efforts- discrete efforts or work products- we never give it a second thought. The people who do it well keep getting more work to do, and those who “don’t get it” (be it scope, schedule and/or resources) do not succeed. It is only when we raise the stakes, do we roll-out this need for “project management”, which is why it is perfect for all these discrete, one-time efforts.

Project Management is ultimately flexible…

You only have to invest in as much project management structure as you need to manage the risk of not achieving your scope, within the the schedule, based on allocated (or most probably, available to you) resources. Getting a letter mailed this afternoon does not carry the risks of say building a house, nor the risks of launching a new product world-wide. However, they are all projects. And, they all have three things in common. They all have: a Scope, a Schedule and some limit on Resources.

When we do encounter higher risk, more complex projects, we can break them down into individual streams of work or we can create separate “work packages” of scope, schedule and resources.

Because each project is discrete, we typically do not spend an inordinate amount of time defining, for example, the scope. Carrying this example, this leaves us some wiggle room on the quality of the deliverable to the customer of the project (as long as we satisfy our “customer’s” needs). Or, if we do spend some time understanding what is required (e.g., scope), how often does it come with a “by Friday” (e.g., schedule) and “only spend two hours on it” (e.g., resources). Hence, we generally have the ability to trade-off between amount of a person’s time, and/or the schedule. It is this continuous trade-off based on developing, potentially unknowable-at-the-start, information we define as project management.

So what does this mean to me?

When you are receiving day-to-day assignments…

- Ask what, when and how much?

- Clarify what is most important, and

- Discuss potential risks and trade-offs you might anticipate.

- If you encounter a trade-off outside of “your pay grade”/agreed framework, immediately discuss situation and the options with your resource manager or the assigning manager

When assigning work…

- Clarify scope, schedule and resources you expect to be accomplished and consumed

- Think about the risks and how much project management structure is necessary and appropriate to help manage/mitigate the risk (e.g., 15% for 1 to 6 man-month efforts)

- Secure project lead (and team as appropriate) buy-in to the scope deliverables, scheduled when and expected resource investment (be it time, equipment, etc.)

- Actively probe the lead and team (informally and formally as appropriate) on key risks and performance

This note has been informed by previous work of the author. See Reeder, Thomas J. (1995), “Take a flexible approach”, Industrial Engineering, March, pp 29-35.